[dropcap]C[/dropcap]omplaining about public transportation is an art form in Bogotá, and not without reason. Fewer than one-in-five of the city’s 8 million residents owns a car, meaning that millions of people take to Bogotá’s buses and sidewalks every day.

As many as 2 million use Transmilenio alone.

That bus rapid transit system in particular is the subject of many a Bogotano’s loathing. But Bogotá doesn’t know just how great Transmilenio really is.

It may not have the iconic recognition or architectural and engineering prestige of the New York Subway or the London Underground, but Transmilenio is nonetheless worthy of pride.

It’s a scrappy, low-cost, high-functioning system that manages improbably to move more than 2 million people per day around an otherwise gridlocked city. It’s a triumph of function over form, and for all its flaws, it works pretty well.

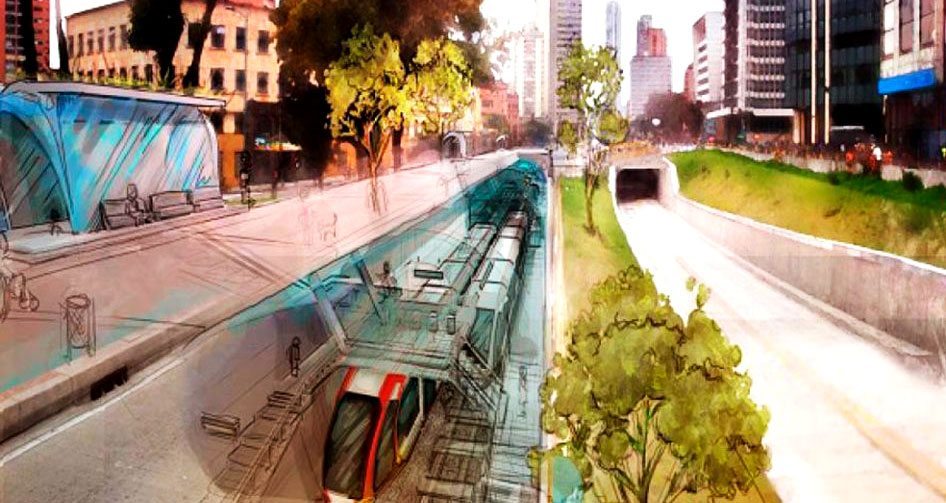

Now, the mastermind of Transmilenio, Enrique Peñalosa is about to return as Bogotá mayor after a 15-year absence. The hottest transit topic in the city is not how to update and improve his pet project, however, but how to build a metro system.

Specifically, should the metro go primarily above or below ground.

One would think that after decades of discussion – and billions of pesos spent – with no concrete action taken, the people of Bogotá would be open to pretty much any metro system they can get.

That’s not the case.

Mayor-elect Peñalosa wants the metro to be mostly above ground, citing lower cost, quicker construction times and fewer engineering challenges.

Recently, he pointed to geographical and urban planning characteristics that suggest it would be best to have an underground metro in the northern part of Bogotá and an elevated section in the south.

Opponents of that plan have said Mr. Peñalosa is trying to sabotage the city’s transit or derail plans for a metro in order to preserve the dominance of his Transmilenio system.

Earlier this week, Bogotá’s current Mayor Gustavo Petro called the plan for an above ground and below ground system discriminatory.

“A high-quality metro in the north and a low quality metro, which could lower property values in the south would be social segregation,” said Petro in a November press conference.

Property values are indeed a concern, but there’s no reason to assume that an elevated metro need be of a lower quality than a subterranean line.

Indeed, above-ground metros are no less prestigious or beneficial than their subterranean counterparts.

Plenty of major cities around the world — including Tokyo, Chicago and Hong Kong —have metro systems that run for at least some distance above ground. Those municipalities are hardly urban planning lightweights.

And there are some substantial advantages to an elevated metro in Bogotá.

First of all, it rains a lot. Sometimes it rains so much that the streets flood in a matter of minutes. Ensuring that subway stations don’t also flood would be an impressive feat of engineering, not to mention one that would be incredibly expensive and completely unnecessary.

Build a metro above ground and the problem is solved.

And flooding isn’t just a trivial concern. It’s been a major problem in cities around the world.

After Hurricane Sandy hit in 2012, New York began investigating how to prepare its aging subway system for the next big storm. A handful of expensive piecemeal solutions like seawalls and tunnel plugs have been tried so far, but the system is still vulnerable.

The stakes are high. Hurricane Sandy dealt at least $4.75 billion in damage to the metro system.

Bogotá doesn’t get hurricanes, of course. Nor is the city anywhere near sea level. And despite its reputation as a rainy city, Bogotá technically gets less precipitation than New York each year on average.

But the city is nonetheless prone to flooding during particularly strong rainy season deluges, especially along Bogotá’s southern and western edges. So floods could be a major challenge for an underground metro system.

Then there’s the question of security.

Crime is still a serious problem in Bogotá, and by far the most common incidents are precisely those that tend to take place on mass transit systems worldwide: muggings and pickpocketing.

It would certainly be possible to make an underground metro safe in Bogotá, though it could easily be a more significant challenge than an above ground system.

But by far the most important advantages to an elevated metro are cost and time.

Subterranean metro systems can cost as much as ten times more than above ground rail systems to build. Recent estimates suggest that an underground rail in Bogotá could cost as much as $563 billion pesos — nearly $200 million USD — per kilometer to build.

That’s roughly in line with other construction costs around the world. Above ground rail systems, on the other hand, tend to cost as little as $12 million USD per kilometer.

In other words, Bogotá could build nearly 20 times the metro system above ground that it could build below ground for the exact same price.

And the concern that elevated rail would negatively impact property values, while a common worry in cities worldwide, is not borne out by statistics. Numerous studies have shown that property values generally increase with proximity to mass transit.

It’s hard to fault Bogotá for wanting the very best metro system possible. Indeed, the city deserves a system worthy of its impressive ongoing makeover as one of Latin America’s most culturally and economically vibrant cities.

But the fight over whether that metro should go above or below ground is ultimately rather silly. Either – or both – would benefit the city.

The only thing a metro really needs to do in order to be successful is to move people around quickly, efficiently and comfortably.

Those are far more important concerns. And in Bogotá, the most important priority of all is that the metro finally gets built.

Share this story

Ed Buckley

Ed Buckley started working with The City Paper in July of 2011 and now runs the paper's website in addition to helping with writing and editing. Ed is originally from Charleston, South Carolina.