Guatavita is a small green lake set in a crater in the hills north of Bogotá. The fact you need to climb up to this very circular body of water is somewhat strange: it doesn’t seem quite natural, and no one really knows how it was formed. A meteorite, maybe? A sink-hole, possibly? More surprising, is that this chilly pond only 300 metres wide spawned the legend of El Dorado, a myth so potent that for four centuries it drove gold-crazed explorers in to every corner of the continent (and many to early graves) and passed into the English language as the lost city of fabled wealth.

The story begins with a boy chosen to be chief, explains our guide as we huddle in the mist on the crater rim looking down at the lake. He lives in a cave for nine years then emerges to take part in an erotic dance with naked village maidens, whom he must manfully ignore. If he passes this test he becomes ruler of the Muisca, an advanced community of farmers and artisans covering a large chunk of the Andes. But first he undergoes an elaborate initiation ceremony to appease the Muisca gods. He is covered in honey and gold dust, sails into the lake on a raft with many attendants, then washes off in the gold lake and throws in some jewellery. Being gold dusted made him golden, El Dorado, the ‘Golden One.’

El Dorado is a person, not a place. This is something of a revelation for me as I always imagined El Dorado as a city lost in the jungle, not a cold lake, and certainly not a kind of pre-Colombian Liberace with expensive taste in skincare.

So how did this Lost City myth start? Perhaps, when Spanish conquistadors were busy grilling locals (in some cases literally) to find their gold. The El Dorado ceremony was already recounted on the Caribbean coast, where the Muisca had trading links, and the locals quickly learned to distract the Spanish with embellished tale of lost cities: “Somewhere over those mountains over there…” in the hope the Spaniards would saddle up and ride on.

Conquistadors didn’t need much convincing. They were so hungry for gold their reluctant hosts concluded they must feed it to their horses. In fact, tons of priceless cultural artefacts were melted down then shipped back to Spain as ingots. This was more than just naked greed; the conquisting business model relied on ever-expanding acquisition. New World expeditions were costly (akin the Apollo moon shots in real terms) and the only kick-starter from the Spanish crown was a “Licence to pillage” with the caveat to send tons of treasure back to Spain. Not surprising El Dorado went viral.

The Spanish had El Dorado on their radar since the 1530s, but it would be another decade before they subjugated the Muisca and founded colonies in the Bogotá plateau. By 1545, the conquistadors had heard first–hand accounts of Guatavita’s ceremonies from Muisca elders. This was the lake of the legend. And how do you find treasure in a lake? Why, empty it of course. Thus started a 400-year assault on the sacred waters to take out what the Muiscas had thrown in; a desecration that claimed many lives of the Muiscas themselves, now destined to work for their Spanish usurpers, in a series of increasingly desperate missions employing ingenious, and sometimes bizarre, techniques to get the gold.

The Spanish made their first attempt in 1545 and set relays of Muiscas scooping out lake water in clay pots, a few decades later 8,000 laborers set to work cutting a huge notch in the crater rim (the remains of which can be seen today) draining out 20 meters of water to find more gold trinkets in the mud before the workings collapsed killing many.

Historical accounts vary wildly on what treasure was found, but invariably describe financial ruin for the Spanish entrepreneurs after the Crown had took its cut of the loot. Over the next two hundred years (and many attempts) noone hit jackpot, but failure it seems just spurred on the gold-crazed colonists, both deeper into the lake and further into uncharted corners of South America.

The El Dorado legend grew like vine and morphed into a ‘city’ then an ‘empire’ that began to appear on maps sent back to Europe. In the colonies of Peru and Gran Colombia the Spanish administrators used El Dorado as a subterfuge to get rid of the meddlesome old Conquistadors who stood in the way of prog- ress: send them to the jungles to find lost empires, with a good chance they might never come back. Such was the fate of “El Loco” Aguirre. His murderous rampage down the Amazon and Orinoco rivers found nothing but death and eventually his own. He was shot by his own troops “his body cut up and bits sent to different cities of Venezuela.”

The British seafarer Sir Walter Raleigh fared little better. Determined to find El Dorado before the Spanish, he skirmished with them in the Orinoco River where his son died in combat, and sailed home to a beheading by King James fed up with warmongering and exaggerated treasure tales.

Back at Guatavita, the search never stopped and things hotted up after a visit in 1801 by naturalist Alexander von Humboldt. This most acclaimed scientist of his day used a distinctly daft method to value of treasure: he measured the lake and estimated that if 1,000 Muisca a year had each chucked in 5 gold objects for over 100 years then there was at least US $300 million-worth of goodies still lurking in the green depths. This calculation was revised upwards by other ‘experts’ to US$ 1.5 billion, a figure published as fact in early travel guides to South America thereby ensuring new generations of treasure hunters.

More attempts to cut through the crater rim and lower the lake level failed, usually with loss of life and financial backers’ investments. Between 1823 and 1826 a local businessman Pepe Paris teamed up with a British navy Caption Charles Cochrane to dig a series of trenches and tunnels. Eventually the tunnel collapsed causing more Indian labourers to perish, and leaving Chochrane and Paris destitute. Back in England, Cochrane clawed a living by singing Spanish songs under the guise of ‘Señor Jean de Vega’ never knowing that nearly 200 years later Iron Maiden would record El Dorado, a heavy metal lament on the lost cause of imagined wealth. It won a Grammy, and possibly went gold.

In 1898 a man called Hartly Knowles formed The Company for the Exploitation of the Lagoon of Guatavita, a re- freshingly honest title later contracted to Contractors Limited. He arrived at the lake with huge fanfare and mule trains carrying the pride of British technology: a very large steam pump. Thus, began an industrial-scale attempt – spanning over a decade – that culminated in a 400 meter shored tunnel from the center of the lake. This channelled water and mud through a sluice system with mercury to capture the gold. By 1904 the lake water was drained but its base was bottomless mud that after hot sun baked hard like cement.

In terms of treasure the pickings were slim, though in 1912 the New York Times ran a detailed report with the fas- cinating note of ‘Chinese jade figures’ in among the Muisca artefacts. But as Knowles relates in the article, most gold found was beaten very thin and did not weigh much. The haul was sold for 500 guineas at Sothebys in London, the company sunk, and natural springs filled the lake back up.

You would think by now that people would just give up. But no! Legend stuck. In the 1930s hard-hat divers floundered around in the mud 30 meters down, a both dangerous an unpleasant task with few rewards, and in the 1950s the lake was dredged with steel balls and clamshell grabs, all for nothing. Then in 1965 the famed US treasure diver Kip Wagner announced Colombian Exploration Inc; destination Guatavita. Kip never showed. The Colombian authorities had enough, the lake became protected and the treasure hunters sent packing.

Standing on the crater I can hardly imagine those years of frenetic toil driven by lust and greed. The lake has an eerie calm, broken only by the chirping of birds. The sun peeps out from the mist and bathes surrounding farmland in green and gold. In the thin chilly air – we are 3000 meters above sea-level – it is easy to comprehend why Andean tribes worshipped the sun. Our guide asks us to honour the Muisca past: we turn our backs on the lake and cup our hands on an imaginary ball of golden light, turn back to the lake and gently blow our golden wish towards the waters below.

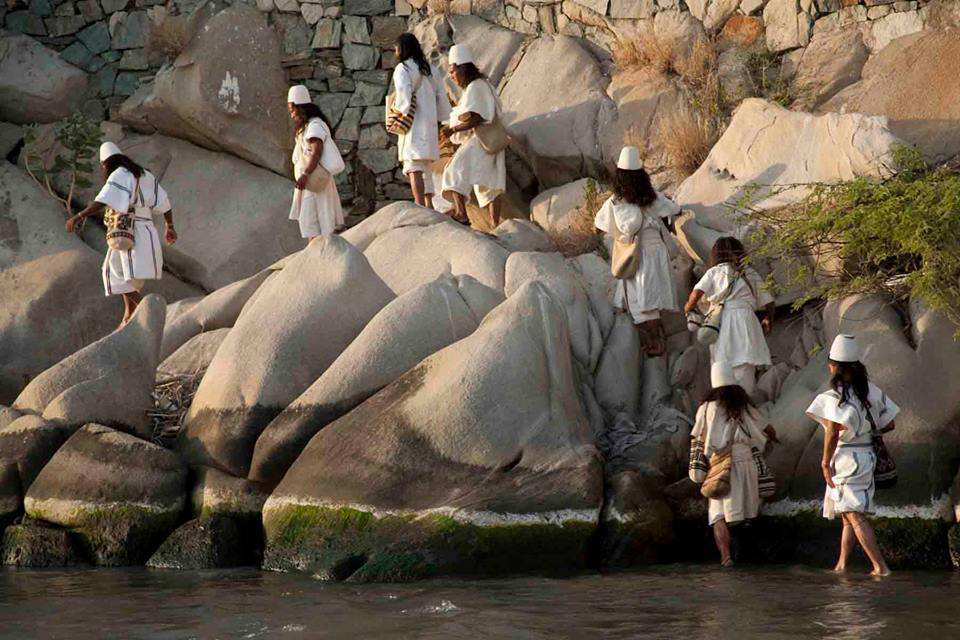

The story turns full circle. Today, Guatavita is managed by the descendants of the Muisca who still live on the slopes. It forms a small park which welcomes visitors who come for the 90-minute guided tour and walk up the steep rim. The lake also seems to be a focus for a small re-discovery of the Muisca culture whose language, Chibcha, was banned by the Spanish in 1770.

So what happened to the treasure? Was there ever any treasure? Von Humboldt’s bad maths overlooked the simple fact that in unlike the Incas and the Aztecs, the Muiscas had no gold mines. The little gold they came from barter. Could they throw that much gold into the lake?

In recent decades satellite imagery has revealed giant earthworks in South America’s jungles that hint at vast human settlements, since swallowed up by vegetation. Some are still waiting to be found, for this is a legend that lives on.

Share this story

Stephen Hide

View all posts by Stephen Hide