[dropcap]W[/dropcap]e have a guest for dinner, a doctor who is expert in alternative medicine. After the plates have been cleared, he takes two plastic vials out of his bag and places them on the kitchen table. They are full of wriggling larvae.

“What are the maggots for?”

“We put them on wounds,” our guest explains.

“Won’t they eat you?” my daughter asks. My son hides his finger, the one with a band-aid, in case he is about to become part of some experiment. They rush out to the safety of the living room.

This short exchange nicely sums up the feeling most people have about maggots. And the thought of sticking the critters in an open wound?

Getting over the first reaction

Dr. Hilderman Pedraza is used to this: “Overcoming people’s negative perceptions of larval therapy is one of the challenges. But when they see the results, they quickly accept it.”

The doctor is currently Colombia’s pioneering advocate of using maggots to help clean and heal wounds. The technique can have seemingly miraculous results in complex and festering infections which resist antibiotics and otherwise require months of painful wound treatments.

It’s a passion that started when he witnessed countless amputations of injured limbs as a young doctor in rural Colombia.

“The sad fact is, as medics we often quickly amputate rather than try and cure serious infections. By cutting off the limb above the infection, the doctors can wash their hands, job done. But the limbless patient is sent home disabled, a burden to the family with more costs for them and social services. I always thought we could do more to prevent losing the limb.”

This conviction took Dr. Hilderman into the world of alternative and Chinese medicine, entomology and larval treatment. Although common in other countries, it is unheard of in Colombia. He had to learn from scratch and even breed his own flies.

Bio-surgery with maggots, he explains, works by placing the 4mm-long white larva of the green bottle fly into the open wound. They then get to work eating the dead flesh, a process known as Maggot Debridement Therapy (MDT) that cleans the area and helps the body’s own defences heal the living tissues.

Better than antibiotics

“But surely,” I reply, “putting bugs in your gashed leg seems to fly in the face of common sense. Wounds are supposed to be clean and sterile, right? Was not the biggest advance of 19th century medicine the discovery of antiseptic surgery? Would not the great surgeon Joseph Lister be choking on his carbolic soap?”

Dr. Hilderman sighs. Well, yes, cleanliness is important; in fact the larvae he uses in his therapy are sterile, bred in strictly controlled labs and fed agar-like jelly. These are VIP maggots, not your rubbish dump variety.

In the last five years he has successfully treated hundreds of patients in his consultation rooms in Palermo, Bogotá, usually with chronic wounds that have proven impossible to heal with normal antibiotics.

This is possible, he explains, because as part of their digestion process, the maggots vomit enzymes that both wash the wound and have strong antibiotic properties, particularly good at overcoming new strains of multi-drug resistant bacteria.

[quote]The fluids secreted by the maggots continue to protect and heal the wound long after the maggots have been removed.[/quote]

One session of larvae therapy, which lasts several hours, can have remarkable effects, says Dr. Hilderman, flipping through some before-and-after photos of patient wounds. In fact, the fluids secreted by the maggots continue to protect and heal the wound long after the maggots have been removed from the wound.

The exact mechanism is still not fully understood, though scientists believe that fly larvae that normally thrive on dead carcasses have naturally developed strong chemicals to deal with the most deadly pathogens.

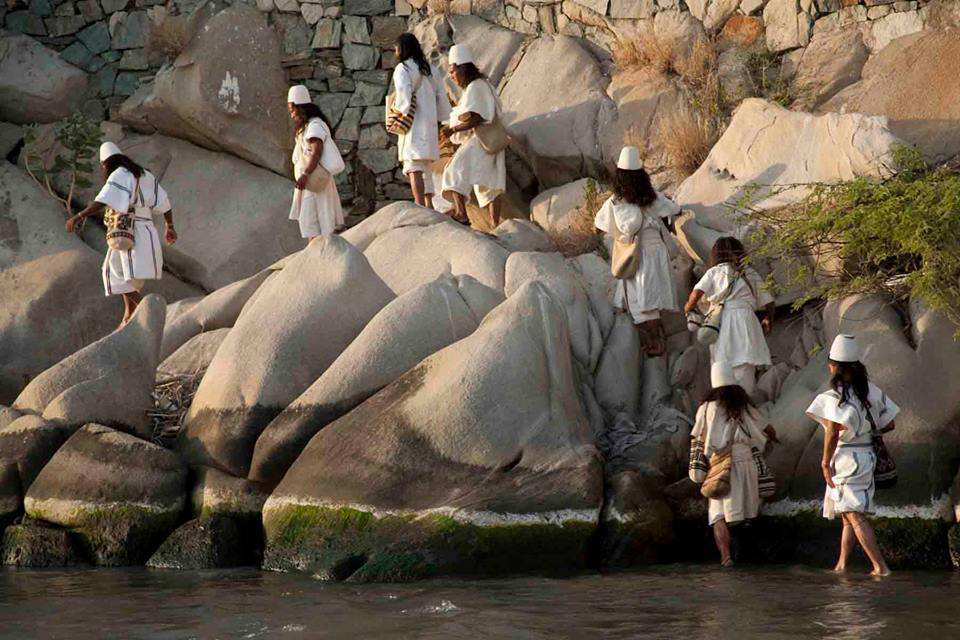

None of this knowledge is new. Many ancient cultures were well aware of the technique, such as the Mayans. Indigenous people such as Australian aboriginals and Burmese hill tribes have long been using larvae therapy. It even gets a mention in the Bible.

Healing with a history

Larval therapy has been documented in European and North American medicine for over 500 years, mostly appearing during large wars such as the Napoleonic or U.S. Civil War when front-line surgeons noticed that fly-blown wounds often healed faster.

But it only entered mainstream medicine after the Great War (1914-18) when 70% of soldiers with open wounds died of infection – and U.S military surgeon William Bauer looked for ways to save lives.

Dr. Bauer developed the larval techniques recognized today with sterile maggots and special net-like dressing to hold them in the wound area. In a groundbreaking experiment in 1929, he successfully treated 21 patients with severe bone infections.

In the next decade more than 300 U.S hospitals started using his techniques.

The rise of the maggot was short-lived though. Mass production of new antibiotic drugs in the 1940s meant the larva technique was largely forgotten, though in the U.S it was sporadically used in hopeless cases where drugs had failed. But maggots wriggled back into the mainstream again in the 1990s when researchers showed improved healing times with larvae in the face of drug-resistant bacteria like MRSA.

Today, larval therapy is a routine and cost-effective treatment available in most developed countries, with factory-scale production of sterile maggots in the U.S and Europe. It has even become a first line treatment for some infections, with specialized larvae-filled bandages being used for up to five days with repeat doses for serious wounds and ulcers.

In Colombia, larval therapy has yet to take off because it is still not officially recognized by our health authorities, despite a six-year battle with bureaucracy by Dr. Hilderman. This leaves the therapy parked on the ‘alternative medicine’ shelf and only available to private patients or in a very few specialized sites like UniValle in Cali.

Bringing maggots into the mainstream

While in legal limbo, the maggots can’t be accessed by needy patients referred by public health providers.

One frustration is that the Ministry of Health seems well aware of its benefits: in response to one of Dr. Hilderman’s petitions, they sent him back their own scientific literature review which talks up the therapy. But still no official recognition.

Part of the problem, he suggests, is legal and technical, namely how to define a maggot: is it a medicine? Is it a device?

“The delays drive me crazy because worldwide this bio-surgery is a recognized treatment for serious wounds. If we mainstream larval therapy, we can reduce amputations, save limbs and save money. Other countries have done it, and so can we,” states the doctor.

Meanwhile Dr. Hilderman has forged his own trail and become an internationally recognized expert on the techniques. He is linked in to a worldwide group of larval therapists.

“What is the risk that amateurs and charlatans getting on the bandwagon?” I ask. I can imagine street sellers starting to hawk maggots alongside football shirts and Diomedes CDs in Galerías.

“That could be dangerous, as they would not be sterile. Also, you need to know your maggots. Only the green bottle fly larvae do the job,” he explains. “Green bottle larvae just eat dead tissue. They are special. Other fly larvae will eat your living flesh.”

I look shocked.

He laughs. “One more good reason for the health authorities to recognize it and control it!”

Share this story

Stephen Hide

View all posts by Stephen Hide