I woke up to orange skies and the smell of sulfur. Located on the banks of the Magdalena River in the department of Santander, Barrancabermeja is home to Colombia’s largest oil refinery, owned by state petroleum company Ecopetrol. Typically referred to as “Barranca,” the perpetually hot and muggy metropolis has long been associated with “black gold,” radical politics, and violence.

As early as the 1530s, Spanish conquistadors spoke of a thick tar bubbling out of the earth in modern-day Barranca, which they used to repair their boats. Several centuries later, the extent to which oil has permeated the city’s culture is clear. The church boasts a drilling rig as its bell tower. A “Petroleum Christ” statue guards the factories. Bustling bars display images of green iguanas, the Ecopetrol logo.

Tropical Oil, a subsidiary of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, acquired the drilling rights for the area around Barranca in 1919. The oil boom created a new working class of migrant laborers, as well as Colombia’s oldest and most powerful industrial trade union. Prior to the company’s arrival, the Magdalena River Valley was better known for indigenous resistance, peasant struggles over land, and refuge for Liberal troops during the nation’s nineteenth-century civil wars.

The National Government dubbed Barranca a “red zone” in the 1990s following clashes between leftist rebels and right-wing paramilitary groups, but today parts of the city could pass for a hipster’s paradise. Walking through the commercial district towards the wharf, I visited century-old barbershops with antique Koken chairs, painted decal signs on vintage soda shops, and backroom billiards halls hosting bright murals of Latin American folk singers.

Thin wooden canoes filled with silver and orange fish floated along the muddy brown river. The Santos administration is currently dredging the Magdalena to cut transportation times and costs. While several men casting large nets agreed that the project would increase efficiency and boost the district’s economy, they also expressed fear that small-scale fishermen would lose out if the surrounding wetlands dried up as a result.

Beside the waterway was a pink luxury hotel built in 1943. Beneath its shaded gardens, elderly women fanned themselves with round and colorful wicker fans that resembled oversized lollipops. Around the street corner, men played cards and drank beer in dozens of small eating holes serving catfish and tilefish with fried plantains. Between the wooden tables, white egrets searched for food scraps.

At dawn the next morning, I drove out with a regional NGO leader past lush green fields and fat grey chigüiros, the word’s largest living rodent, towards the department of Cesar. A Barranca native with salt-and-pepper hair, he had once studied to become a priest but instead organized student protests. Dirt roads were flanked by palm oil mega-plantations, which have replaced the once traditional rice, corn, and cotton crops.

Over scrambled eggs and flatbread arepas at a roadside eatery, he told me in a hushed voice about guerrilla infighting, local mafia structures, and nearby cocaine laboratories. Arriving to the municipality of Aguachica, he pointed out the street where men loyal to alias “Megateo,” chief of a splinter rebel group and one of Colombia’s most feared drug lords, had abducted a resident businessmen in broad daylight last April.

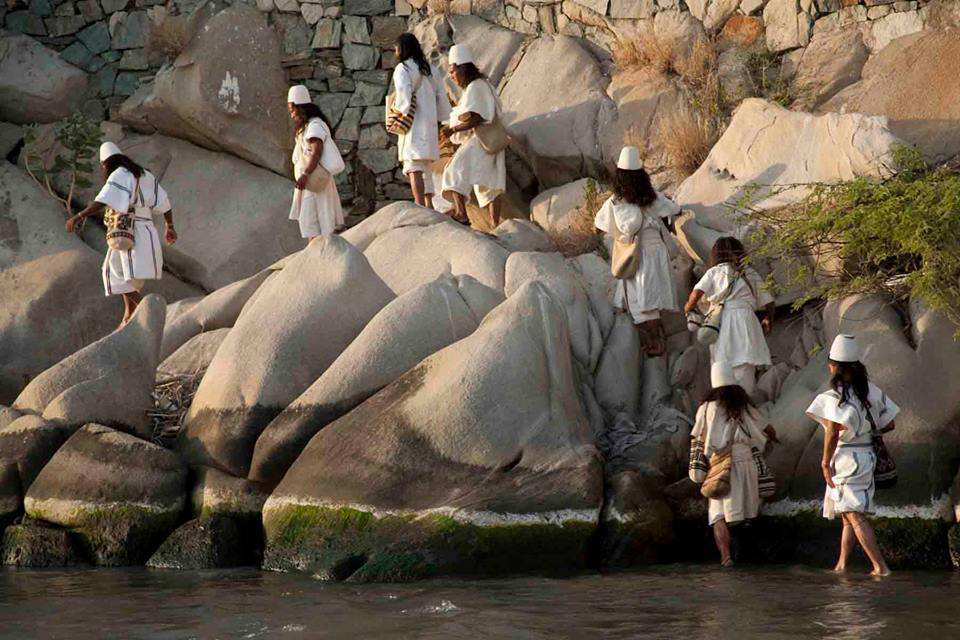

We met with about one hundred farming and indigenous representatives involved in legal battles with the government over ownership of land titles. On a two-hectare plot lawfully held by one of the participants, families had erected makeshift shelters from logs of wood still patched with bark. Beneath a twelve-meter long thatched roof of dry leaves, they sat in colored plastic chairs and discussed next steps.

A stone’s throw away, hundreds of armed men camped out on a privately owned plantation filmed the ongoing assembly. At dusk, a young supporter of the farmers approached a plainclothes man that was bearing a pistol, asking for his employer. The presumed paramilitary member slipped behind the gate and was replaced promptly by a member of the town police. “There was no man without a uniform,” he said.

With night falling, cicadas buzzing, and thunder rolling through the skies, the peasant leaders recounted tales of injustice by guerrilla and paramilitary groups, both of which have been responsible for mass displacement throughout Colombia’s armed conflict. “We can buy your property from you or your widow,” appears to have been an oft-repeated phrase, accompanied by the clicking of an imaginary trigger.

On my way back to Bogotá, with the car’s headlights illuminating young escorts waiting by truck stops, I struggled to imagine bloodshed amid such scenic nature. In the distance, the conference over, farmers engaged in traditional tambor dances adopted from nearby Venezuela. Colombian author Laura Restrepo’s famed description of Barranca came to mind: “the city of three p’s: putas, plata and petróleo”: prostitutes, money, and oil.

Share this story

Alden Pyle

View all posts by Alden Pyle