This weekend, members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) gathered for their first “National Guerrillas Conference” since 2007. This 10th edition of the insurgent group’s most important recurring event is unique for two reasons.

One is that it is the first to be held openly. After more than a half-century spent hiding from the military in the jungles and hinterlands of Colombia, and after four years of successful peace negotiations in Havana, the guerrillas are now free to convene in public. Mainstream reporters were even allowed to roam around an event that the rebel faction’s leaders — despite looking defeated militarily are speaking of triumph.

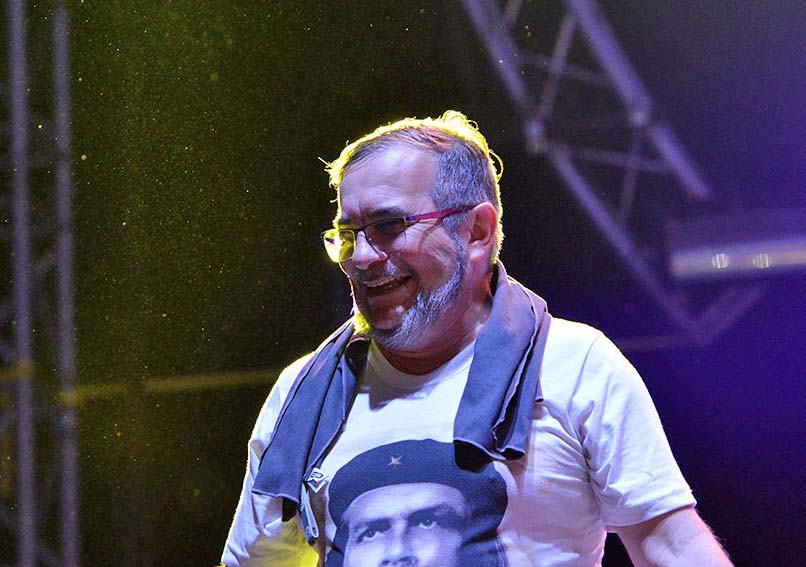

Amid the some 200 members who travelled to the rural plains of Llanos del Yarí, top FARC commander Rodrigo Londoño Echeverri, alias “Timochenko”, said that his forces have “resisted the longest and most violent onslaught launched by the imperial power” against a guerrilla army. He said that “it’s definitely clear that in this war there are no victors or defeated.” And he noted that “our opponents are forced to recognize our full rights to political exercise, with the broadest guarantees.”

That is the other reason this 10th conference is historic. It will be the FARC’s final meeting as a criminal organization.

As a condition of the already-finalized peace accord, which will be formally signed on September 26 during a ceremony in Cartagena, FARC will lay down its arms and transition into a political party. That’s why they are meeting. In addition to ensuring that the rank and file will comply with the agreement, the commanders have gathered to discuss FARC’s future as an organization that will participate in a democratic government.

For FARC, this was a critical component of the peace deal. For Colombians, this remains among the deal’s most contentious provisions.

Many cannot accept that a group that has, for generations, caused so much death, pain, and destruction will become legitimized. And they plan to voice their dissent in the simple yes-or-no plebiscite that will be held on October 2 and is intended to ratify the final accord.

Government officials recognize that this is hard to swallow. But Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos, who has staked his political career on achieving peace, said that he expects FARC to find few supporters as a political party.

“Unless they modernize their speech and modernize their mission, I don’t see much success in their political ideas,” President Santos told the New York Times. “But the whole purpose of this process is to allow them to try.”

To further show its desire for reconciliation after conflict that saw the death of at least 220,000 and displacement of seven million more, FARC recently offered a near-unprecedented apology. In 2002, it kidnapped 12 local officials in Valle del Cauca and held them hostage for more than five years. Then, out of nowhere, it announced that 11 had died in captivity.

“We will not evade our responsibility,” said the senior FARC representative “Pablo Catatumbo” at an event on September 10 to admit these wrongs. “They were in our hands. The death of the deputies was the largest absurdity of what I have lived in war, the most shameful episode. We are not proud of it. Today, with sincere humility, we make a public acknowledgment and we ask for forgiveness. I hope you forgive us.”

Apologies are not nearly enough for many Colombians. The nation’s most recent former president, current Senator Álvaro Uribe, is leading the “No” campaign to undo the work done by Santos, his one-time friend and former defense secretary. “No” billboards that have both been erected in Medellín, among other locations, depict FARC leaders alongside Cuban head of state Raúl Castro. They visually equate acceptance of the accord as acceptance of Marxist militancy.

The government has staunchly rejected any notion that the agreement is letting war criminals get off with impunity. FARC leaders will face a tribunal and a sentence of up to eight years, not in jail, but with restrictions on their freedom.

It isn’t the manner of justice generally levied against those who did such unspeakable things. In August, Colombia’s lead negotiator Humberto de la Calle admitted the the deal does falls short in some regards. “Surely the accord we’ve achieved isn’t a perfect accord,” he said from Havana. “But with the same honesty and frankness with which we’ve informed public opinion, now I want to make clear that I have certainty that it is the best possible accord. We all probably would have wanted something more.”

For most, the deal is good enough. A Datexco poll taken last week has the “Yes” vote holding strong at 70.5%. But the opposition questions the rationale for accepting a lukewarm compromise when FARC laying down arms may not change the on-the-ground reality.

For one, there will be dissidents. The government estimates that up to 10% of guerrillas will not submit to peace. Most visible are 40-odd members of the “First Front” who have pledged to go on fighting. An AFP report states they have been enticed to stay in the jungle to tap potentially lucrative gold-mining sites.

There are also informal guerrillas. While estimates of the official FARC fighting force fall between 6,300 and 7,500, there may be up 13,000 including affiliated militia members who “operate clandestinely and semi-autonomously from the rebels’ military structure.” Colombian General Javier Flórez expects an undetermined number within these forces to refuse to demobilize.

Then there is the National Liberation Army (ELN). Reports from across the country say that the nation’s second-largest leftist guerrilla group is bolstering its presence in former FARC-held areas, including Nariño.

Some have hoped that the ELN would use today’s climate of forgiveness to sign a similar peace deal and end its fight. But the fallout from its high-profile kidnapping this summer of Spanish-Colombian journalist Salud Hernández-Mora, who has urged Colombians to vote “No,” seems to have pushed the faction further towards belligerence.

Bogotá-born Íngrid Betancourt, who was kidnapped in 2002 while running for president and held by the FARC for six years, has taken the opposite view. In an interview on French television, she recognized that the justice guerrilla commanders face will not provide traditional vengeance and leave them behind cold, iron bars for life. But despite her personal struggle to forgive her captors, she only sees one path forward for Colombia.

“We need to fly up and try to not think in the suffering we had but in what we’re sparing our children and the future generations to live,” said Betancourt to France 24.

From Paris to Llanos del Yarí, millions are hoping a “Yes” vote will formally put this conflict in the past. Others, from Bogotá to New York, will vote against an imperfect peace.

In such a politically charged time, it is surprising that “Timochenko” until recently, an enemy of the state, could be the one to offer a message that can resonate with everyone.

“In your hands,” said “Timochenko” in his opening remarks at the final FARC conference, “lies the fate of Colombia.”

Share this story

Jared Wade

View all posts by Jared Wade