When Oscar Alejandro Pérez-Escobar walks through a rainforest, he does not just see green. He sees evolutionary stories unfolding leaf by leaf, petal by petal. For him, orchids are not only some of the most dazzling plants on Earth but also sentinels to understanding how life diversifies and adapts.

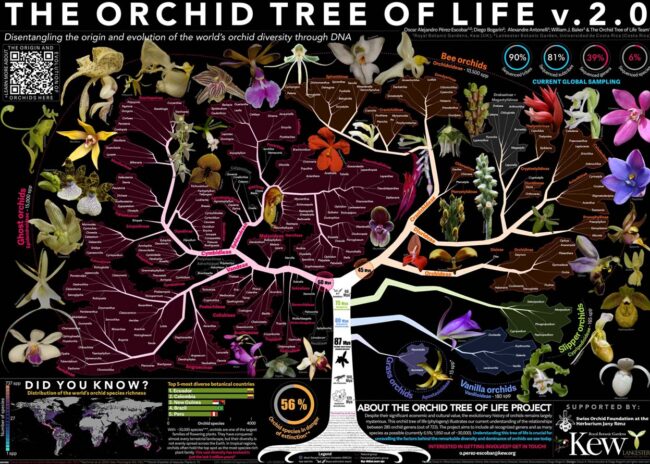

Most recently, Pérez-Escobar has published a landmark paper in New Phytologist, The origin and speciation of orchids, involving 48 co-authors across 15 institutions and three continents. The study represents the second major milestone of the Orchid Tree of Life project, which Pérez-Escobar leads as a Research Group Leader at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Its ambition is extraordinary: to build the most comprehensive orchid phylogeny ever assembled, tracing the evolutionary history of more than 700 genera and documenting relationships among over 30,000 orchid species worldwide – and counting.

“This paper was not just about building a tree but about building a strong network of collaborators, friendships and combining knowledge to develop new hypotheses on where and how orchids originated,” Pérez-Escobar says.

The scale of the project reflects both the grandeur of its subject and the urgency of the times. Orchids, one of the largest families of flowering plants, are under growing threat from habitat destruction, climate change and illegal trade. By reconstructing their evolutionary history, Pérez-Escobar and his colleagues hope to inform global conservation strategies – ensuring that future generations will still marvel at the dizzying diversity Darwin once described as “among the most remarkable of all orchids.”

Campoalegre to Kew

Pérez-Escobar’s path to Kew Gardens began in Colombia, one of the most biodiverse countries in the world. Growing up in Bogotá, he would explore the dense Andean cloud forests with his late grandfather and parents. As a student, he vividly remembers living among orchids that would “fall with twigs from trees”, in the University’s forest reserve at Yotoco (Valle); nestled in the rugged folds of the Central Cordillera of the Andes.

A decisive moment came in 2005, during a field trip for his undergraduate degree in Agronomy Engineering at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia. There, he met Gamaliel Ríos, a local farmer – campesino – and forest guardian. Wandering through the forest with Ríos, Pérez-Escobar was stunned by the abundance and complexity of orchid species.

“I kept asking myself: why are there so many orchids here? Does this happen elsewhere in the Andes?” he recalls. “That curiosity, sparked by his generosity and love for orchids, led me down the path of orchid systematics – and eventually phylogenetics, macroevolution and genomics.”

After completing his studies in Palmira, Valle del Cauca, he moved to Germany to pursue a doctorate at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. His research explored the evolution of sexual systems in the Catasetinae orchid – a subject that Charles Darwin himself had described with fascination more than 150 years earlier. Pérez-Escobar graduated in 2016, the same year he joined Kew Gardens as a postdoctoral researcher and Sainsbury Orchid Fellow. By the age of 30, he had been appointed Research Group Leader – a rapid ascent that speaks to his scientific drive.

Today, he not only steers the Orchid Tree of Life project, but also coordinates the Taxonomic Expertise Network on Tropical American Orchids and serves as trustee of the Swiss Orchid Foundation.

Darwin’s observations of tropical flora has laid much of the groundwork for modern evolutionary biology. His studies of orchids revealed their ingenious pollination strategies and deep ecological interdependence. For Pérez-Escobar, carrying that legacy forward is both a responsibility and a confirmation. “We are finding that what Darwin believed with orchids, is true, 150 years later,” he says.

If Darwin’s insights provided the foundation, Kew Gardens provides the modern stage. A UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the world’s most important botanical institutions, Kew holds over eight million preserved plant specimens and living collections unmatched in diversity. For scientists like Pérez-Escobar, it is a vital resource – part museum, part laboratory, part sanctuary – where research can inform both science and conservation.

Behind Pérez-Escobar’s achievements lies a personal story of determination. Growing up on a small farm in Valle del Cauca, his parents cherished their role as harvesters of the fruits and staples that sustain Colombian households. At age 15, he faced a life-defining choice: to study agronomy at the public university in Palmira, or remain on the farm. He chose study, as his vocation was stronger that the pull of the land. “Science and research gave me purpose,” he says. “The chance to learn deeply about a subject, to contribute knowledge, and to use it to protect the biodiversity I grew up with.”

That sense of purpose continues to fuel his role at Kew. “I am also deeply motivated by the big picture: working across disciplines to ask bold questions and tackle urgent challenges,” he writes in the academic journal. From naming a new species to uncovering the three-tried sexual systems in orchids, Pérez-Escobar sees his work as part of a larger struggle against biodiversity loss.

“We are living in the midst of a climate and biodiversity crisis, and I strongly believe that science must meet this moment. That means stepping beyond the academic bubble, engaging with society and producing knowledge that can inform conservation, inspire action or shift how we see the natural world.”

Although orchids remain his central passion, Pérez-Escobar also studies culturally and economically important plants such as coca, where until now, some 250 species have been documented. But orchids, with their fragile beauty and evolutionary endurance, remain his greatest fascination.

“Orchids have outlived the dinosaurs, but they are ‘canaries in a coalmine,’ as we like to say, given that their survival within an ecosystem is very complex and depends on many external factors. If one deforests a hectare of forest, the orchid can never be replaced. The extinction of the orchid is devastating, but more devastating to us, as they are essential in maintaining biodiversity. Everything is interconnected in the survival of an orchid. Ochids are fundamental in helping us understand climate change.”

Among the groups that captivate him most today are Lepanthes, a genus of some 1,200 miniature species, many of which employ sexual deception to lure pollinators. More recently, he and his colleagues discovered a rare case of sexual dimorphism in some Lepanthes species — the first such finding since Darwin described it in other orchids more than a century and a half ago.

Such discoveries illustrate why Pérez-Escobar’s work resonates far beyond taxonomy. By combining genomic datasets, herbarium specimens and field observations, he bridges past and present, uncovering how plants have adapted over millions of years. His vision is clear: to use science not only to map the tree of life, but to safeguard it.

As he reflects on his journey from Colombia’s cloud forests to leading cutting-edge research at Kew, Pérez-Escobar is keenly aware of the broader stakes. “Ultimately, I am motivated by the idea that the work we do, no matter how specialized, can ripple outward; that our research can serve people, protect biodiversity and contribute to a deeper appreciation of life on Earth.”

The Orchid Tree of Life poster is freely available for download at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27021472.v2

Read the most recent interview of Oscar with the prestigious scientific journal The New Phytologist at: https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.70484