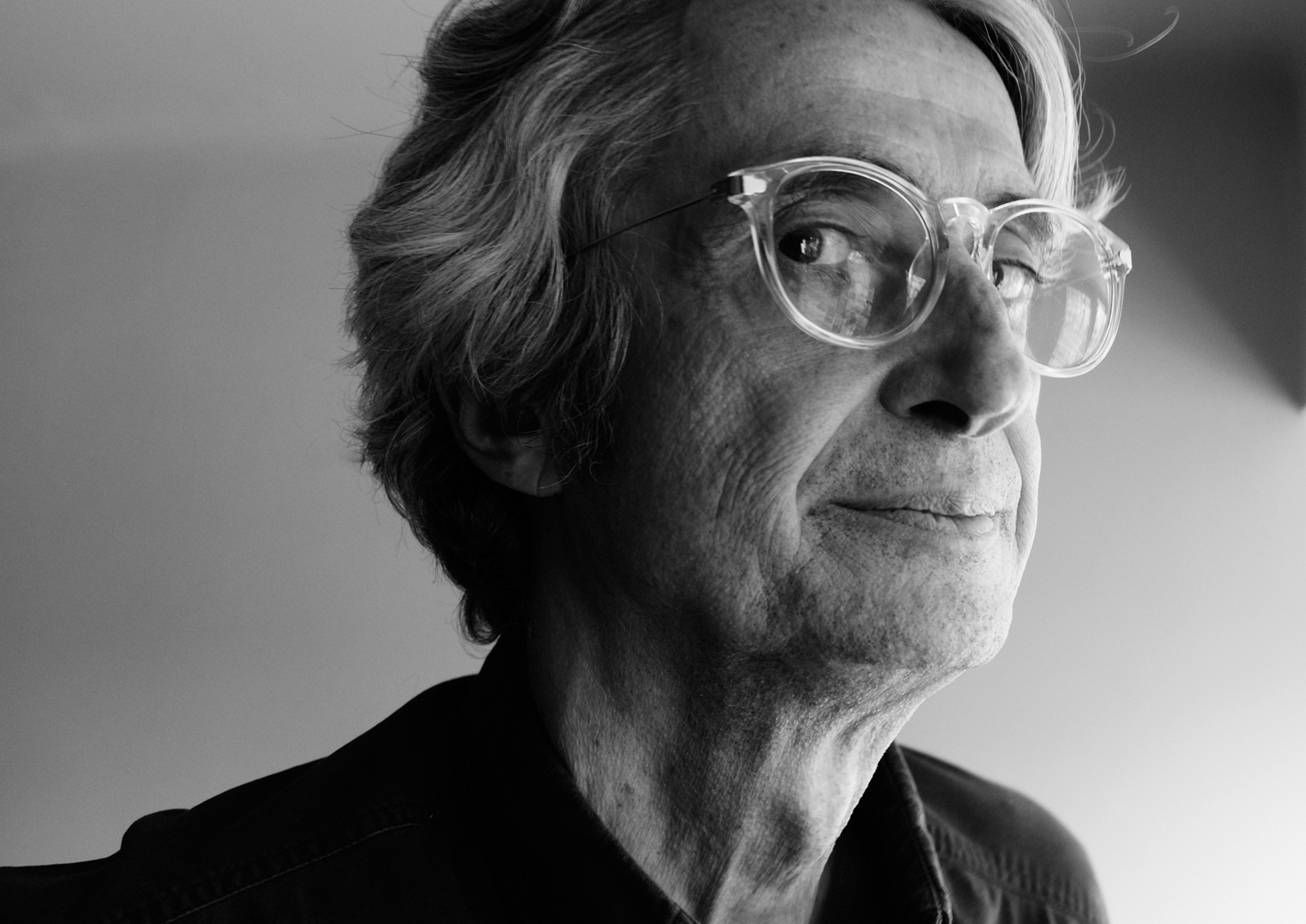

The celebrated Colombian filmmaker Luis Ospina has died after a long battle with cancer. In 2016, Ospina gave an extensive interview to The City Paper titled Reflections of Caliwood.

During much of the 1970s, Cali underwent a cultural revolution of sorts. This city of parks, tree-lined boulevards, cafe?s, movie clubs, and galleries became a meeting place for Dadaists challenging the genteel artistic foundations of their sugarcane-based capital.

Throw anarchists and aspiring filmmakers into this anti-art movement, and you have a shaken and stirred cocktail of creativity.

While Bogota? boasted its universities, Cali was a tropical agora of social thinking — or rather, anti-establishment thinking — infused by the sounds of salsa and seduced by silver screen classics such as Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane.”

For Luis Ospina, born in 1949, the departmental seat of Valle del Cauca was home, where he studied at a bilingual school with a very “Anglo-Saxon” education. He then finished his baccalaureate in Boston in May 1968.

“It was a very memorable date,” he remarks, recalling the mass marches of students, teachers, and workers an ocean away in the French capital. These protests, which turned to riots, betrayed a world hijacked by youthful idealism and left-wing rebellion. A brick thrown from the Paris barricades reverberated in the consciousness of the world.

Ospina headed west to Los Angeles, and took up film studies, first at the University of Southern California, and then at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

But Cali was his lebensraum or California Dreaming. In 1971, while at UCLA, he teamed up with his close friend, Carlos Mayolo, to shoot a 16mm documentary titled Oiga Vea (Hear, See) rooted in the social exclusion surrounding the VI Pan-American games underway in their hometown. “May 1968 arrived in Colombia in 1971,” remarks Luis, and like a poet once said “everything arrives late in Colombia, even death.”

“And like a poet once said: Everything arrives late in Colombia, even death.

They shot their short from the perspective of the people outside the stadium, the Afro-Colombians who could only observe the high dives from street corners, and those who could only afford to ride on the Pan-American train, but not afford an entry ticket.

“We felt our city would change with these games,” he said. “The powers that be decided to transform this idyllic place, the most Americanized of all Colombian cities.”

There was an urgency to Ospina’s visual experiment of “counter-information” and in 27 minutes, Cali became a catalyst for the future of Colombian filmmaking. Luis Ospina was at the heart of Cali’s cultural revolution and through their newly formed film club, Cali Cine Club, a young writer stepped into the scene.

Andrés Caicedo would give his words to their movie magazine, Ojo al Cine, and go on to become a literary icon in Colombia’s sub-culture centrifuge. The protagonists who lived in the hippie neighborhood Ciudad Solar became known across the land as the Cali Group.

Their inspiration: Caliwood, a creative force that would last two decades.

“There was absolutely no financing for making films in Colombia,” recalls Ospina of his original budget of $36,000 pesos for Oiga Vea. But the exercise in socially motivated storytelling resulted in a spate of shorts and made-for-television documentaries.

In 1978, Mayolo and Ospina released a “porno-misery” turned social critique: Agarrando Pueblo. Caliwood had taken a stance. Poverty and the mercantilism of the film industry to win international awards was cross-examined. “Vampires of Poverty” went on to receive its share of cultish acclaim.

Before Hollywood fell in love with vampires, Ospina released in 1982 his allegorical thriller Pura Sangre, a commentary on the vampirism at the heart of capitalism in Latin America. Made with B Movie bravado and a virtually non-existent budget, Pure Blood put the filmmaker and his Caliwood cinematic pied pipers first and foremost in the minds of movie goers. “Cali was the pioneer of film in Colombia,” reaffirms Ospina.

Caliwood went on to create an invaluable body of work within the context of Latin American film. Ospina, Mayolo, and Caicedo were almost inseparable movie-making musketeers. Tragically on March 4, 1977, Caicedo committed suicide.

A decade later, once respected as one of Colombia’s most important documentarians, Ospina paid tribute to his friend in his 1986 personal film essay, Andre?s Caicedo: Unos Pocos Buenos Amigos.

In the late 1980s, Cali came under threat from a much more ominous and dangerous force than filmmaking. A powerful drug cartel was imposing its narco laws, gaudy architecture, and new- money aesthetics upon the 1 million inhabitants of the city.

For many, including Ospina, “Cali was disappearing for the worse.” A diaspora of artists began to flee narco culture and seek creative refuge in the capital of Bogota?. “By 1991, everyone had left Cali,” reflects Ospina.

“I was one of the last of Cali Group to stay.”

That same year, Carlos Mayolo was also wrapping up for the private television channel RCN a poignant television miniseries based on the sugarcane industry of the Valle del Cauca. “The end of Azucar was the end of Caliwood,” said the pioneer.

Ospina packed up and moved to Bogota?, leaving behind the city that made him. Despite years of disenchantment with Cali, he continued to be an inspiration for a generation of future filmmakers and spokesperson for the city’s important cultural undertakings.

He helped establish the film and social communications faculty at the Universidad del Valle became director of the Cinemateca of the Museum of Modern Art La Tertulia and artistic director of the Cali International Film Festival.

Between his commitments to students and writing, Ospina was the beneficiary of many cultural awards, including the Ministry of Culture Lifetime Achievement Award in 2010.

From Bogota?, Ospina’s documentaries became more long-term and more intimate in their focus. Death and the fragility of life became dominant themes. In 1993, he released Nuestra Pelicula (Our Film) based on the last interview of the Colombian neo-expressionist painter Lorenzo Jaramillo.

Two years later, the director concluded 10 historical episodes of Cali: ayer, hoy y mañana (Cali: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow) ending an exhaustive visual journey with his beloved city.

Celebration of a life’s work

“There’s evolution in my work” said Ospina on the eve of the premiere of his latest work “Todo comenzó por el fin (It All Started at the End)” at the 56th Cartagena International Film Festival (FICCI).

Shown to audiences last year at the Toronto Film Festival (TIFF), Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, and Mar de Plata Film Festival, Ospina in 208 minutes recounts his ordeal with gastrointestinal stromal (GIST) cancer while trying to rescue archival footage from the Cali decades. He underwent surgery and chemotherapy just after production began.

“The film is long because I wasn’t counting on getting sick. When I realized how serious this illness was, I couldn’t just focus on my past. I needed to look to the future. My clinical future.”

Shot in different mediums during a span of five years, Todo comenzó por el fin” is a testimony to Ospina’s fight with cancer and confronting a possible end-of-life situation. “I was virtually dead,” remarks Ospina. “It became a life project for me. I thought it was the summing up.”

During the 56th version of the International Film Festival of Cartagena (FICCI) Luis Ospina will receive the most prestigious honor and recognition for his 45 years of contributing to Colombian film. “They are giving it to me in life,” he laughs.

In a year when Ciro Guerra’s “Embrace of the Serpent” was nominated for an Oscar in the Best Foreign Language Film category and “La Cie?naga Entre el Mar y la Tierra (Between Sea and Land)” won an Audience Award in the World Cinema Dramatic category at the Sundance Film Festival, Ospina downplays his stature among Colombia’s emerging directors.

“I think we in Caliwood were a bad influence.”

Ospina’s death obsession may also be waning as his health improves and he actively prepares to take his 208 minutes to prestigious festivals around the world. But the past is ever present in his intense autobiographical work.

“I was fortunate to live at a time when young people believed they could change the world. Today, young people are concerned with trying to save the planet.”

Taking on universal themes has set Luis Ospina apart from the directors of his generation. Even though he will always be “that sick little boy,” he is well on the road to recovery and ready to receive the first-ever tribute from FICCI for a Colombian filmmaker.

Guided by the maxim of sex, drugs and movies in “Todo comenzo? por el fin,” the founding member of an artistic movement that transformed the documentary genre has come of age and is unabashed of the vicissitudes of his life.

“With this, I close a loop,” he says. And even though he long exorcized the Cali Group, the memories of a golden age in Colombian cinema live on as translucent celluloid in the stories of a lost utopia. This is the true reflection of Caliwood.

Share this story

Richard Emblin

Richard Emblin is the director of The City Paper.