For centuries, the funerary masks of Colombia’s Eastern Andes have guarded their secrets. Crafted from resin, clay, wax, maize, and adorned with delicate beads, these masks were fitted so precisely to the faces of the dead that the mummified bodies appeared almost alive. Between the 13th and 18th centuries, the Muisca — an Indigenous civilization that once flourished across what is today Bogotá, with its high-altitude Sabana, and the department of Boyacá – developed elaborate burial rites that fused artistry with spiritual belief. Their masks were more than ornaments: they were portals between the living and the afterlife, preserving identity even as bodies were interred.

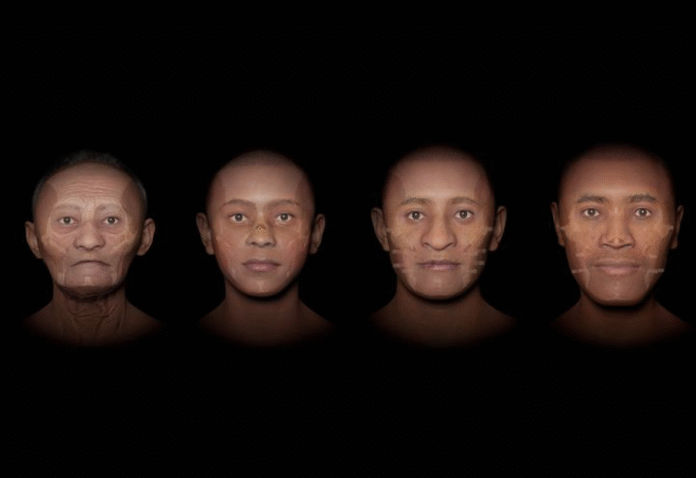

This summer, those ancient faces have been revealed once again – not through excavation, but with digital tools. At the XI World Congress on Mummy Studies, held in Cusco, Peru, in August, researchers from Liverpool John Moores University unveiled the facial reconstructions of four individuals whose mummified remains are housed at Colombia’s Institute of Anthropology and History (ICANH). Using cutting-edge forensic techniques and three-dimensional modeling from Face Lab scientists digitally “removed” the masks for the first time, revealing lifelike portraits of people who lived centuries ago.

The project, supported by the British Academy, was led by Professor Caroline Wilkinson and Dr. Jessica Liu, specialists in craniofacial reconstruction. “We are thrilled and privileged to be involved in this project which highlights the fascinating cultural practices of the Indigenous peoples of South America,” said Liu in the University’s official statement. “We hope that revealing the faces for the first time increases interest in these incredible civilizations.”

The masks, described by archaeologist Dr. Felipe Cárdenas-Arroyo of the Colombian Academy of History as “of extraordinary workmanship,” are the only known examples of their kind in Colombia. Made directly onto the anterior aspect of the skull, they cover the entire face and jaw, merging skeletal structure with crafted form. Although some are damaged – noses chipped away, sections along the base missing – their precision and ornamentation speak to sophisticated funerary traditions.

Little is known about the four individuals themselves. Their graves were looted long ago, severing critical archaeological context. Radiocarbon dating places their lives between 1216 and 1797, during the later pre-Hispanic and early colonial periods. They include a 6- or 7-year-old child, a woman in her sixties, and two young men. All are believed to have belonged to a Muisca community in the plateaus of the Eastern Cordillera.

To reconstruct their faces, the Face Lab team began by performing computerized tomography (CT) scans on the masked skulls. CT scanning uses multiple X-ray images to create detailed three-dimensional models, enabling researchers to “digitally unmask” the skulls by removing the mask layers virtually. “Because of this, the team could effectively unmask the skull digitally,” Liu told journalist Sophie Berdugo of Live Science.

Once unmasked, the team used specialized software and a haptic stylus to superimpose layers of soft tissue – muscles, fat, and skin – onto the skulls. For the two men, they used average facial tissue depth data from modern Colombian men. For the woman and the child, lacking specific local datasets, they made informed estimates. “It’s like virtual sculpting,” Liu explained. “You use the scaffolding of the skull to get the tissue to perfectly fit the individual.”

After shaping the anatomy, the team chose skin tones, hair, and eye colors typical of people from the region, then added textural details like pores, freckles, eyelashes, and wrinkles. These elements produced remarkably lifelike portraits. Yet Liu is quick to clarify that the reconstructions are scholarly interpretations rather than definitive likenesses. “Texture is always the biggest challenge,” she told the science publication. “We simply don’t know how they would present themselves, whether or not they have any facial scarring or tattoos, or if that actually is the skin tone. What we present in terms of texture is an average representation, based on what we know of these individuals.”

For Colombia, the digital unmasking represents both a scientific breakthrough and a cultural homecoming. By revealing the faces of individuals from the distant past, researchers have provided new ways of connecting with a civilization that shaped the Andes centuries before Spanish colonization. “The masks are of extraordinary workmanship and so far, the only ones known to exist in Colombia,” emphasized Cárdenas-Arroyo.

In the months since their unveiling, these reconstructed faces have traveled far beyond the conference halls of Cusco. Shared on Instagram, digital heritage platforms, and museum networks, the images have reached audiences across the globe. AI-assisted tools have even made it possible to animate these digital portraits, giving the impression of blinking eyes and subtle expressions. Viewers often remark on the uncanny resemblance between these ancient individuals and contemporary Colombians, despite the passage of time.

Through the fusion of ritual, science, and digital technology, pre-Columbians are no longer faceless figures consigned to the past. Their reconstructed portraits serve as powerful reminders of human continuity, circulating widely online and inviting a global audience to encounter them anew.