Hernando García grows coffee in Colombia. He also raises maize and beans on his small farm in Cajamarca, a valley known throughout the country as the food basket of Colombia. His land is some of the richest agricultural soil in all of South America, land that is blessed with abundant clean water year-round.

[otw_is sidebar=otw-sidebar-7]

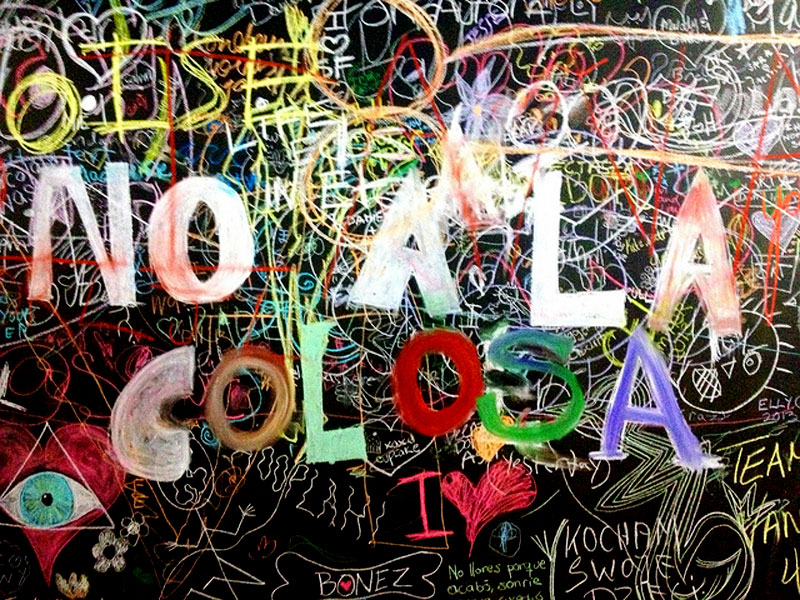

His fertile land also sits atop what is believed to be one of the richest undeveloped gold reserves on the planet: thirty billion dollars’ worth of gold. La Colosa is the colossal international mining project that may soon begin turning Hernando’s land and his neighbors’ land and water into gold. La Colosa may also turn his land into a colossal environmental and cultural disaster – a modern example of “reverse alchemy.”

La Colosa is potentially the largest environmental disaster that no one has ever heard of. And the developers of this massive strip-mining project want it to remain their well-guarded secret. For this reason and others, there has been very little reporting of this pending environmental disaster in any mainstream media outside of Colombia; in fact, very little reporting of it even within Colombia.

Gold has always flowed through Colombia’s veins – literally and figuratively. Since the beginning of time the indigenous peoples of Colombia have viewed gold as the precious blood of their Earth Mother.

In the sixteenth century the Spanish conquerors arrived on Colombia’s shores, searching for the elusive gold of El Dorado to fund the wars of European kings, queens and popes. For the indigenous peoples of Colombia, ‘Columbus’ was not an historical figure but an event, an event that happened only yesterday in their minds, and which continues today. ‘Columbus’ for them is five hundred years of killing the people and destroying the land – and taking the gold. La Colosa is simply a continuation of that ongoing Columbus disaster for the indigenous peoples of Colombia and South America.

What would development of this colossal gold mining project mean for the area, for the local population, for the environment? The London-based human rights organization, Colombia Solidarity Campaign published a detailed report about La Colosa, the AngloGold Ashanti gold mining project in Tolima, titled: “La Colosa: A Death Foretold.'”

The report unveils findings which clearly show that if the production phase of the La Colosa gold mine goes forward, its implications to local communities and the environment would be nothing short of catastrophic. The process of exploitation proposed by the mining company would include open pit mining also known as blasting. This process consists of three steps: mountain or pit blasting, rock crushing, and leaching.

The actual gold exists only in small amounts in the mountain rock, deposits almost invisible to the human eye. It’s extracted by excavation using explosives and heavy earth-moving equipment. Dust produced by the explosions would impact flora and fauna in the surrounding areas, affecting ecosystems, crops, and contributing to pulmonary disease in nearby populations. It’s sort of the gold-mining equivalent of ‘fracking.’

The resulting crushed rock is sorted into a lot of powdery debris and a small amount of mineral gold. The debris is left in heaps while the gold ore is crushed to dust. Then it’s mixed with water and chemicals such as cyanide to separate the gold from other minerals. This process, called leaching, uses large quantities of water and produces highly toxic waste. Environmental groups have estimated that for every one gram of gold, an amount no bigger than a grain of rice, a thousand gallons of water would be used – roughly the same amount of water a local family would use in a year.

La Colosa would require more water and electricity than the minimum domestic consumption of the entire Tolima department whose population is 1.4 million.

Mining waste – rock, dust, and spent water – may eventually exceed 4 million tons a year. Compare that to the mere 2 million tons of waste generated by the entire city of Bogotá in one year. The mining operation would totally consume the fertile land and the clean water of Tolima’s Cajamarca valley.

The people of Tolima know this and many are united in their opposition to the project. “But anyone who opposes mining at the moment is a persecuted person,” says Carmen Sofía Bonilla, former director of the environmental authority of the Department of Tolima.

Locals who oppose the industrial project are aware of AngloGold Ashanti’s reputation worldwide. In 2011, Greenpeace awarded the South African mining company its Global Public Eye Award as the world’s worst company in environmental terms.

Porfirio Garcés, 74, a local farmer says, “The mining company fooled us. There is a serious social division today due to this mine. This is truly a life or death issue. We want to keep our culture based on coffee production, where honesty reigns. We do not want a mining culture based on destruction.”

In July of last year local citizens exercised their right to a referendum as stipulated in the Colombian Constitution. In the Piedras community, the area where the actual leaching process would take place, 99.2% voted against the La Colosa mining project. The government, however, has largely ignored the referendum results. The official government position is that the local authorities have a say over the surface land, the top soil, but that the mineral rights below the surface belong to the federal government. And it’s difficult to imagine the government of President Santos ignoring a potential 30 billion dollar windfall.

Preliminary exploration is underway in the valley. Even this preliminary exploration requires drilling, explosives, and water leaching. A temporary stoppage was ordered by the local environmental council, but illegal water lines have been discovered indicating that exploration, and the water leaching that accompanies it, continues largely unabated.

Local residents have staged vocal protests recently, with peaceful marches and signs asking “Water or Gold?” Farmers and indigenous leaders have little confidence in the government’s ability or political will to halt the destructive mining operation. They’re concerned that peaceful protests may escalate into violence.

The next step is the government approval or disapproval of an environmental impact study. The Report issued recently by the Colombia Solidarity Campaign is an effort to shine a public light on that approval process in the hopes that the true environmental impact of La Colosa will be considered, and that a colossal environmental and cultural disaster can be avoided.

As she works in her vegetable garden, Inéz Yagarí says: “We are very worried about mining here. If they take our lands, where will we go? This is not a jungle, but a protected forest reserve. We must fight for our territory or else our children will be left without land. The foreigners who come here will find trouble. We respect the land. We want to be respected. I hope they don’t come, and that the government will also respect our land and our sovereignty.”

About the author: JOHN LUNDIN is an environmental writer and activist. He is the author of THE NEW MANDALA – Eastern Wisdom for Western Living, written in collaboration with His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and is currently writing a spiritual and environmental novel with the indigenous Elders of la Sierra Nevada.