[dropcap]S[/dropcap]cientists have confirmed that the Pacific Ocean entered the El Niño phase of a cyclical phenomenon that can have wide-ranging effects on global weather.

While this buildup of warmer waters in the southern Pacific comes and goes in natural multi-year cycles – often with no severe consequences – many believe this time will be different.The leading governmental authorities on weather in both the United States and the United Kingdom have stated that the current El Niño may be unlike anything anyone under retirement age has ever seen.

“We’re predicting that this El Niño could be among the strongest El Niños in the historical record dating back to 1950,” said Mike Halpert, deputy director of the Climate Prediction Center of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, in an August press conference.

Many scientists are comparing the current incarnation to the 1998 version, which a recent Oxfam report says caused droughts, floods, and forest fires that resulted in 2,000 deaths and caused $33 billion in property damage worldwide.

In South America it caused $3.5 billion of economic losses in Peru, for example, which saw fishery exports drop by 76%, according to the United Nations Environmental Program.

The defining characteristic of El Niño, however, is uncertainty. Even how often if appears is a mystery, rotating with its sister phenomenon La Niña roughly every three to seven years.

In South America, El Niño tends to cause torrential rains on the Pacific coast and drier-than-normal conditions along the Caribbean. The reverse is true in Central America, with a wetter Caribbean coast and droughts on the Pacific. But the cycle lacks predictable patterns that pass scientific rigor.

It comes down to considering, as Ivan Jorge Ramirez of the New School in New York puts it, “what might be foreseeable.”

Understanding that caveat, a 2007 study from Colombia’s Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies stated that El Niño can reduce rainfall on Colombia’s Caribbean coastline from between 30-50% and cut precipitation by 20-30% in the Andean region.

Such a shortage would touch almost every part of life in the country.

“That has implications for potable water supply,” said Ramírez. “It might have implications for agriculture and hydropower. Colombia is highly dependent on hydropower, so if the water-supply is altered then you have energy-use changing, and that access will then have an impact on all aspects of society.”

Transportation, landslide risk, and the fishing industry are other areas that could be impacted.

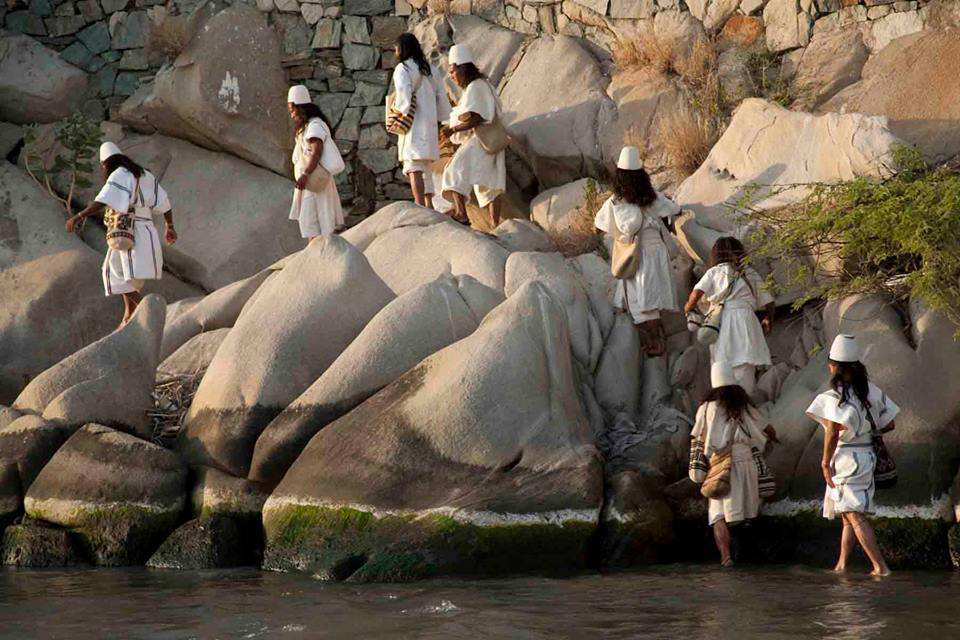

Most troubling of all is how a stark drop in rainfall would devastate La Guajira, the arid peninsula that juts into the Caribbean in northeast Colombia. The impoverished region of 900,000 is largely populated by the Wayúu indigenous community, which has been reeling from a drought, corruption and mismanagement-induced crisis for years.

At least 5,000 children have already died of malnourishment since the start of 2013 due to a lack of food and water, so any additional environmental strain will only make this catastrophe more tragic.

[quote]At least 5,000 children have already died of malnourishment since the start of 2013[/quote]

Another consequence could be the effect heavy rains have on the incidence of malaria and other mosquito-borne illnesses. The nation has cut the disease’s death rate in recent decades, but an uptick in both 2007 and 2010 shows that periodic outbreaks still prove deadly.

Conclusive research into El Niño’s effects on malaria remains sparse (and even more so for yellow fever, dengue, and chikungunya), but research from Columbia University in New York shows some evidence that unseasonable rainfall in southern Africa in 1995 led to a spike in cases.

Flooding can cause other health concerns, too. Ramírez, for example, studied the potential link between El Niño rains in 1998 and a cholera outbreak in Piura, Peru. He noted that cholera is no longer found in Colombia, but heavy flooding could lead to other waterborne, diarrheal diseases in rural, impoverished areas of the country where people lack access to clean water.

“The relationship between El Niño and health is pretty well studied,” said Ramirez. “There’s a lot more we need to understand about it, but we have some generalities that we can say about El Niño and how it can impact health.”

It also creates economic problems. Historically, El Niño years have correlated with years of higher inflation and food-price volatility in Colombia. Between 1960 and 2005, El Niño years saw the price of food fluctuate by 21% compared to 15% in years without the presence of the phenomenon, according to the Colombia’s central bank.

Weather effects outside of the country may also increase the grocery bill of Colombians. El Niño has global weather implications and food is a global commodity. So droughts in Australia, heavy rains in California, and flooding in Chile can alter the agricultural supply-and-demand equation.

“It may not take much of a weather-induced disruption in global food supply to trigger another surge in prices,” states a report from Japanese financial company Nomura.

The firm’s index of countries most vulnerable to global food price spikes ranks Colombia 34th. The average Colombian family allocates just 17.9% of its household spending on food, which compares favorably with the nations that are truly at risk.

But Colombia is still (if just barely) a net importer of food, so inflationary pressures and the low value of the Colombian peso mean that a prolonged jump in prices could put more stress on bank accounts from Cartagena to Bogotá.

Nobody knows how hard El Niño will hit Colombia or any other region on the planet. Every time it rears its head, there is some fallout, but the question is whether the weather will be as volatile this time as some scientists believe.

But if it proves severe, everything from water to food to health to wallets will feel the phenomenon.

Share this story

Jared Wade

View all posts by Jared Wade